By Weronika Szymańska

In a city where incoming students rush to purchase a Cineville Pass faster than you can say “action,” and the annual IDFA festival transforms Amsterdam into a cinematic mecca for thousands, the Dutch capital can pride itself on having one of the most developed cinema landscapes in Europe. Within this expansive art scene, the spotlight shines brightest on student-led cinemas, effectively blending Amsterdam’s youthful spirit with its passion for cinematography.

Student-led places appear to thrive among Amsterdam citizens – its wide student community eager not only to participate in city life but also to contribute to its pace. “Before moving to Amsterdam, I had never been to student-run spaces. I am sure there are some but maybe they are less accessible,” says Panka Bognar, a third-year Humanities major, referring to her home town. It is no different regarding the cinema scene. Damien Robledo Poisson, a second-year Science major, admits that “Amsterdam is pretty much the first time when I see such a big student community around film.” They both agree that the accessibility of student-led cinemas does not rely solely on their prevalence but also on the financial benefits they offer — with notably lower prices for tickets or beverages, student-run venues provide entertainment to suit every pocket. On top of that, their visitors find those places much more inspiring and comforting than the regular blockbuster theatres: “I think you just exist in a space differently if you know you are surrounded by people who do this because they are fond of cinema and they are your age,” Bognar notes.

A vital aspect of art house cinemas is their political involvement. Since many of them stem from protest movements, such as an anti-Nazi resistance group that further formed Kriterion in 1945, they continue to be involved in various initiatives supporting human liberation. Amelija Sokolovskaja, a second-year Humanities major, agrees that “these places are crucial to our environment here and need to be cared for and supported.” She notices how student-led cinemas make education more available and less isolating, emphasising that “it’s a blessing seeing how important conversations can be held through such an accessible and beautiful medium as film.”

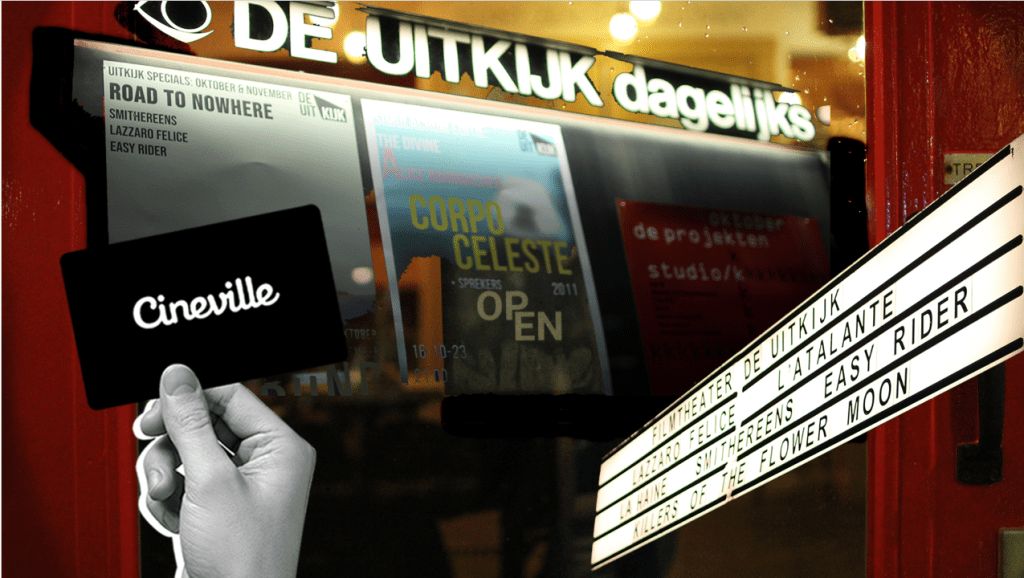

Inass Merzouk, a Rietveld Academie student working in De Uitkijk cinema, highlights how important it is for her workplace to incorporate activism into navigating the projects organised by the venue. “A normal company would have corporate people making those kinds of decisions. Here it all comes from within us,” Merzouk states. With its recent public announcement of solidarity with Palestine and a donation made to Medical Aid for Palestinians, as well as its previous initiatives in support of Ukraine, De Uitkijk makes a clear statement on the significance of the art industry’s involvement in the fight for freedom.

The political involvement of student-led cinemas carries a core educational value as well. Not only do they aim to make a public statement regarding the matters they care about, but also to provide space for those underrepresented, and educate on the topics that are often overlooked. Maja van de Griendt, a third-year Social Science major working in the movie theatre Studio/K, lists initiatives coming into life at this neighbouring venue: programs on the queer movie scene, screenings of Asian short films, discussions about the rights of sex workers and trans people, to name but a few.

Such unprecedented quality for most mainstream theatres goes even further as those cinemas happen to become party venues as well. “One of the great things about student-led cinemas and events is that you have many more hybrids between them — after the screening of a certain movie you have a talk, but there is also a themed movie and a party,” Robledo Poisson claims. They argue that those places let people with similar interests mingle and make other artistic visions come to life.

Despite being art spaces at their core, student-led cinemas oftentimes serve as bars and restaurants as well. Robledo Poisson notices how the interdisciplinary nature of those places often leads to them being primarily known as a community space rather than a movie theatre.“I know people who were going to Kriterion a lot before they actually realised it’s a cinema,” they say. This does not clash with the artistic message they aim to popularise. “If they are getting customers through the fact that they are a bar it doesn’t mean that this customer cannot become a movie watcher afterward,” they claim. Additionally, van de Griendt admits that cinemas, especially the arthouse ones, face financial challenges – diversifying their income through offering gastronomy services is one of the ways to stay on the market. She confesses that “everyone feels the grief when we are at the monthly meeting and we look at the break-even and we didn’t make the profit this time,” which forced Studio/K to moderately increase their prices. Nevertheless, the enthusiasm to make their workplace flourish remains intact due to the devotion they developed towards it, in spite of all the difficulties.

If it was not for the financial help from the generous philanthropist, De Uitkijk probably would not reopen its doors to the audience in 2007 after previously facing bankruptcy. Despite the resurgence, this student-run cinema still needs to face multiple challenges, including those posed by the limited size of their venue: “Because we only have this one screening room, if a distributor wants us to play the movie, for example, four times on one day, we cannot do that because then we cannot play any other movie,” she explains. Nevertheless, she finds those obstacles truly enriching, cherishing everything she has learnt through the job. As her co-worker Jara says, “We are all quite inexperienced, so we’re all really learning on the job, which is super fun […] You are kind of free to make mistakes and figure it out on the go.”

Not many people are aware of the self-sufficient nature of student-led cinemas. Their workers are people wholeheartedly engaged within running the company. “I think some people don’t realise that we literally do everything ourselves. It’s not just students working here at the bar and giving you drinks, but then we run this whole place,” Merzouk emphasises. From creating a programme, through operating the film projector, to managing electricity and conducting social media – those full-time students are led by their passion for cinema to independently run the venues. The organisational structure is democratic and non-hierarchical, with everyone being able to introduce their ideas and carry out the initiatives they root for. As De Uitkijk’s employee notes, however, “shared responsibility is no responsibility,” and everybody holds a specific function to amend the team’s agency.

What makes student-run theatres special is not only what we as an audience derive from them – they stand out because of the approach their employees themselves exhibit, abounding with devotion and love towards the workplace. “I have been thinking about it – why do we all want this to work so bad? We have our problems. But I think that’s the nice thing about it and, once again, I don’t think you will find that in another place,” van de Griendt states. This personal dedication is visible in their relationship with the audience as well, breaking the formal façade often encountered in art venues. “You really get happy if everybody has a nice evening and you really feel like you’re sharing the evening with them,” Merzouk admits smiling. She remembers the times she was a visitor of De Uitkijk herself, when the intimacy created by the workers giving a short talk about the movie before the screening made the experience far more special. “I do think that’s also kind of what the students bring to this place, a more personal experience,” she observes.

To the disappointment of many, in a city as nationally varied as Amsterdam, student-led cinemas hire only Dutch speakers. “I believe this could and should be remodelled as there are many great non-Dutch speaking activists and film enthusiasts who could bring these places even further in the industry,” Sokolovskaja explains. She does admit, however, that she understands why those institutions decide to sustain this working model. “I find it kind of a problem how much the Dutch language disappears from social life and working life, and I feel in most other countries you wouldn’t be like, oh, why do you have to speak French to work here in Paris?” Jara notes.

As all of inner communication is conducted in Dutch, the democracy of student-led cinemas requires similar proficiency in the language used in order to express oneself freely and exclude power dynamics. Moreover, since the history of the place strongly relies on the national heritage, they are not willing to give up on what influences their work so greatly. “I just love the Dutch language and we want to have the meetings in Dutch, we want to keep this Dutch image,” van de Griendt stresses. Despite the regret, Robledo Poisson acknowledges that their presence in the company structures would eventually force them to shift to English, as well as create power dynamics, and they do not feel in a position to dictate that. “I’m already so delighted that I get to be a part of their greater community as a customer. I think they are already giving me a lot,” they say.

With a strong film community present at AUC, visible through the vibrant activity of the CUT committee or the interest that Film Lab and other film courses draw, the student-led cinemas appear to be crucial both in acquiring the knowledge and experiencing the power of art. Robledo Poisson admits that they consume a great number of movies owing to the venue offered for them by those student initiatives. They contribute to film education either through presenting old or contemporary classics, as well as giving a platform to the pieces that go unnoticed, Sokolovskaja explains. The interconnection between AUC and student-led cinemas seems to appear among their workers too, with van de Griendt asserting that “if I look back on my AUC career, I will always think of Studio/K.” Although due to the heavy workload in both of those occupations this combination tends to be perceived as infamous, van der Griendt believes the experience she derived from both of them remains priceless. “They kind of belong together because in my first month of AUC I started working at Studio/K and if I graduate, I will probably stop working there as well, moving to a different part of the city,” she concludes.